Hunting and fishing drive conservation

For over 80 years, sportsmen and women have played a crucial role in funding conservation efforts in the United States through the American System of Conservation Funding (ASCF). The American System is a “user-pays, public-benefits” structure, unique to the rest of the world, in which those that consumptively use public resources pay for the privilege, and in some cases the right, to do so. This funding System has allowed the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation to become recognized as the most successful conservation framework in history.

Resources

Hunting and fishing support land, water conservation

Each year, hunting and fishing-related activities generate approximately $3.3 billion for state-based conservation in the United States. These resources have been used to acquire, manage, maintain, and conserve roughly 24.5 million acres held under fee title ownership by state fish and wildlife agencies. In addition, these agencies have improved nearly 57 million additional acres for the benefit of wildlife and their habitat through agreements with private landowners.

Research published by scientists at the University of California-Berkeley has found that 33% of the 440 million privately owned acres in the United States is used for wildlife-associated recreation, including hunting and fishing. Hunters in particular, use larger, intact privately-held properties and contribute significantly to the $17 billion that Americans spend to access or own private land for wildlife-associated recreation. In addition, landowners that generate income from wildlife-associated income are more likely to participate in government conservation programs. This relationship between the public’s demand for access to high quality, intact habitat and their willingness to pay for it demonstrates the importance of thoughtfully considering incentive structures for private land and water conservation when developing strategies to achieve the 30 by 30 Initiative’s objectives.

In addition to championing recent policy successes like the Great American Outdoors Act and the America's Conservation Enhancement Act, hunters' and anglers' commitment to land and water conservation remains a critical asset. Since 1934, 6 million acres have been acquired using Federal Duck Stamp (required to hunt migratory waterfowl) revenues. More than 300 national wildlife refuges were created or have been expanded using Federal Duck Stamp dollars. Hunters and anglers work tirelessly to support programs such as the Farm Bill’s conservation title ($6 billion), North American Wetlands Conservation Act ($60 million), the Land and Water Conservation Fund ($900 million) and National Fish Habitat Partnerships ($7 million) represent a substantial component of conservation delivery across the nation and their impact is multiplied many times over through matching requirements that leverage non-profit fundraising and private sector investment in conservation.

Research published by scientists at the University of California-Berkeley has found that 33% of the 440 million privately owned acres in the United States is used for wildlife-associated recreation, including hunting and fishing. Hunters in particular, use larger, intact privately-held properties and contribute significantly to the $17 billion that Americans spend to access or own private land for wildlife-associated recreation. In addition, landowners that generate income from wildlife-associated income are more likely to participate in government conservation programs. This relationship between the public’s demand for access to high quality, intact habitat and their willingness to pay for it demonstrates the importance of thoughtfully considering incentive structures for private land and water conservation when developing strategies to achieve the 30 by 30 Initiative’s objectives.

In addition to championing recent policy successes like the Great American Outdoors Act and the America's Conservation Enhancement Act, hunters' and anglers' commitment to land and water conservation remains a critical asset. Since 1934, 6 million acres have been acquired using Federal Duck Stamp (required to hunt migratory waterfowl) revenues. More than 300 national wildlife refuges were created or have been expanded using Federal Duck Stamp dollars. Hunters and anglers work tirelessly to support programs such as the Farm Bill’s conservation title ($6 billion), North American Wetlands Conservation Act ($60 million), the Land and Water Conservation Fund ($900 million) and National Fish Habitat Partnerships ($7 million) represent a substantial component of conservation delivery across the nation and their impact is multiplied many times over through matching requirements that leverage non-profit fundraising and private sector investment in conservation.

Hunting, fishing and 30 by 30

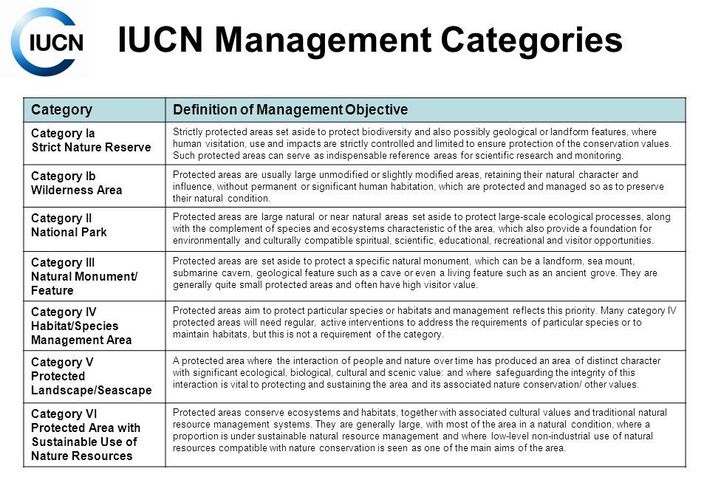

IUCN Protected Area Categories (IUCN)

IUCN Protected Area Categories (IUCN)

Defining Protection, Targeting Species Needs

Globally, the 30 by 30 Initiative promotes increased habitat protection and restoration and national and regional conservation strategies with a goal of promoting and protecting biodiversity worldwide. 30 by 30 proposals are linked to global land and water protected area targets established by the United Nations Convention on Biodiversity (CBD), and ongoing efforts to encourage nations to establish more ambitious targets when they gather at the next Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 15).

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s World Commission on Protected Areas defines "protected area" as a “clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.” Protected areas can take many forms ranging from a “hands off” approach that strictly limits human visitation, use, and impacts to areas actively managed and manipulated for the benefit of specific species to defined areas managed to sustainably conserve ecosystems in concert with cultural and socioeconomic needs. As 30 by 30 proposals are considered at the local, state and federal levels, the full range of protected area categories should be considered and defined, providing focused direction to address species needs using the full suite of conservation actions that will maintain or enhance biodiversity how and where it is needed most. Failing to define the range of management categories and governance structures that constitute the protection of the ecosystems identified by the 30 by 30 proposals creates uncertainty for the hunting and fishing community, private and commercial landowners, and local communities, as well as the natural resource managers tasked with implementing policies that further the goal of the initiative itself.

Defining “protection” is consistent with the CBD itself, which includes provisions stating that parties to the treaty agree to “[d]evelop, where necessary, guidelines for the selection, establishment and management of protected areas or areas where special measures need to be taken to conserve biological diversity.” Further, CBD parties have agreed to “[r]egulate or manage biological resources important for the conservation of biological diversity whether within or outside protected areas, with a view to ensuring their conservation and sustainable use,” a management paradigm that has much in common with the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation that is broadly supported by the hunting and fishing community. Consistent with this approach, 30 by 30 proposals' definition of “protected areas” should include different management categories that allow for active management and sustainable use with the goal of protecting habitat for the conservation of biodiversity.

Globally, the 30 by 30 Initiative promotes increased habitat protection and restoration and national and regional conservation strategies with a goal of promoting and protecting biodiversity worldwide. 30 by 30 proposals are linked to global land and water protected area targets established by the United Nations Convention on Biodiversity (CBD), and ongoing efforts to encourage nations to establish more ambitious targets when they gather at the next Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 15).

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s World Commission on Protected Areas defines "protected area" as a “clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.” Protected areas can take many forms ranging from a “hands off” approach that strictly limits human visitation, use, and impacts to areas actively managed and manipulated for the benefit of specific species to defined areas managed to sustainably conserve ecosystems in concert with cultural and socioeconomic needs. As 30 by 30 proposals are considered at the local, state and federal levels, the full range of protected area categories should be considered and defined, providing focused direction to address species needs using the full suite of conservation actions that will maintain or enhance biodiversity how and where it is needed most. Failing to define the range of management categories and governance structures that constitute the protection of the ecosystems identified by the 30 by 30 proposals creates uncertainty for the hunting and fishing community, private and commercial landowners, and local communities, as well as the natural resource managers tasked with implementing policies that further the goal of the initiative itself.

Defining “protection” is consistent with the CBD itself, which includes provisions stating that parties to the treaty agree to “[d]evelop, where necessary, guidelines for the selection, establishment and management of protected areas or areas where special measures need to be taken to conserve biological diversity.” Further, CBD parties have agreed to “[r]egulate or manage biological resources important for the conservation of biological diversity whether within or outside protected areas, with a view to ensuring their conservation and sustainable use,” a management paradigm that has much in common with the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation that is broadly supported by the hunting and fishing community. Consistent with this approach, 30 by 30 proposals' definition of “protected areas” should include different management categories that allow for active management and sustainable use with the goal of protecting habitat for the conservation of biodiversity.

Resources

What's already protected?

Once 30 by 30 proposals have defined the protected area management categories or designations that apply to the 30 percent objective, they should also identify currently protected lands and waters that fit within the definition. If this information is not readily available, proposals should explicitly define a process to inventory existing protected lands and waters through credible research conducted by a government entity, and ensure that findings are easily accessible by the public. This inventory should consider not only the size, but the conservation values of currently protected areas within a state. This information is necessary to understand the current scale of protection within a state and assess progress towards achieving the 30 by 30 objective. In addition, this information will contribute to the initiative’s goal of biodiversity conservation by allowing resource managers to target habitats for protection that will more effectively conserve fish, wildlife and terrestrial, wetland, aquatic, and marine resources where conservation actions are needed most.

Once 30 by 30 proposals have defined the protected area management categories or designations that apply to the 30 percent objective, they should also identify currently protected lands and waters that fit within the definition. If this information is not readily available, proposals should explicitly define a process to inventory existing protected lands and waters through credible research conducted by a government entity, and ensure that findings are easily accessible by the public. This inventory should consider not only the size, but the conservation values of currently protected areas within a state. This information is necessary to understand the current scale of protection within a state and assess progress towards achieving the 30 by 30 objective. In addition, this information will contribute to the initiative’s goal of biodiversity conservation by allowing resource managers to target habitats for protection that will more effectively conserve fish, wildlife and terrestrial, wetland, aquatic, and marine resources where conservation actions are needed most.

30 by 30 aims to protect land and water. What else is needed for biodiversity?

Using financial resources generated by the sporting community, federal law requires state fish and wildlife agencies develop State Wildlife Action Plans (SWAPs) that identify Species of Greatest Conservation Need, or those experiencing the threat of significant population declines. SWAPs also identify these species’ habitats and major threats, as well as actions needed to restore and maintain viable populations of these species. For many years, SWAPs have acknowledged the value of biodiversity, identified biodiversity challenges, and defined prescriptive actions necessary to address them. In fact, the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ Best Practices for State Wildlife Action Plans recommends that their member state agencies “strive for a comprehensive, multiscale approach and direct conservation efforts toward biodiversity” when developing SWAPs.

Given that state fish and wildlife agencies have been developing and implementing SWAPs for upwards of fifteen years, and that these SWAPs incorporate habitat protection and biodiversity conservation as primary objectives, management strategies and needs beyond land and water protection should be considered when defining protected area goals (such as through the 30 by 30 Initiative), as part of a larger, comprehensive biodiversity strategy.

It should also be noted that land and water protection does not necessarily translate to enhanced biodiversity. According to research published by the National Academy of Sciences, although the U.S. has one of the oldest and most sophisticated land protection regimes in the world, “United States protected areas do not adequately cover the country’s unique species,” and “major progress in conservation will require actions in both the public and private sectors, and will succeed only if done in the correct areas.” Fortunately, state fish and wildlife agencies have gathered detailed information regarding threats to biodiversity that can inform land and water protection goals through implementation of the conservation strategies outlined in SWAPs. It is both critical to the success of such proposals and efficient given the quality of data that has already been collected by state agencies for 30 by 30 proposals to contain focused direction to address species needs through the previously identified land and water conservation measures and protected area definitions that provide natural resource professionals adequate flexibility to deliver meaningful conservation under a variety of scenarios, including those that call for active management and or restoration to meet fish and wildlife habitat needs while providing ecosystem services for people.

Resources

Identifying funding needed to achieve goals and enforce protections

Many state natural resource agencies rely largely on funding generated by wildlife-associated recreation, such as hunting and fishing, for the conservation of fish, wildlife, and habitat. 30 by 30 proposals should outline anticipated new costs associated with pursuing their objective (e.g., acquisition of land and water resources, conservation tax incentives, management, maintenance, recreation administration, personnel, enforcement). In addition, proposals should include prescriptive language making it clear that implementation of the 30 by 30 initiative beyond the inventoried baseline of protected lands and waters shall not divert funding from the state’s existing conservation and natural resource management activities.

Defining management responsibilities and authorities

Without a clear delineation of the parties responsible for implementing activities in pursuit of 30 by 30 objectives, as well as tracking progress, the likelihood of achieving these goals is reduced. State fish and wildlife agencies are uniquely positioned to coordinate implementation of these activities if provided with the resources necessary to do so, with the participation of local communities, Indian Tribes, federal agencies, non-governmental organizations, private landowners, and neighboring states. Across the country, these agencies employ approximately 11,000 biologists with nearly 6,000 of these employees holding advanced degrees and 741 holding terminal degrees such as a PhD. Tasked specifically with managing public trust resources, these agencies have the scientific expertise and the experience needed to combine and leverage resources, bring stakeholders together, and pursue goals across jurisdictional boundaries within and across states.

Including operative language stating that properly administered wildlife-associated recreation is valuable to the state and consistent with land, water, or ecosystem protection

Given the foundational roles that hunting and angling have played in conserving ecosystems in every state throughout the country, the value of these activities, both historically and currently, should be expressly noted in 30 by 30 proposals. This statement should be included in operative sections of statutory proposals to ensure that hunting and angling access is clearly recognized to coexist with the 30 by 30 initiative’s goals as well as the CBD (in which parties have agreed to “[p]rotect and encourage customary use of biological resources in accordance with traditional cultural practices that are compatible with conservation or sustainable use requirements”). In addition, proposals should acknowledge the dollars and volunteer hours the hunting and fishing community invests in private, federal and state funded programs and the voluntary habitat restoration efforts of private landowners. Such acknowledgment will serve to further encourage these efforts.

A truly successful 30 by 30 initiative will connect individuals – including current users as well as new users and underserved communities – with their environment. The hunting and fishing community asserts that the most effective way to accomplish this goal is to maximize the availability of opportunities to access and utilize such resources for the benefit of current and future hunters, anglers, and all outdoor recreation enthusiasts.